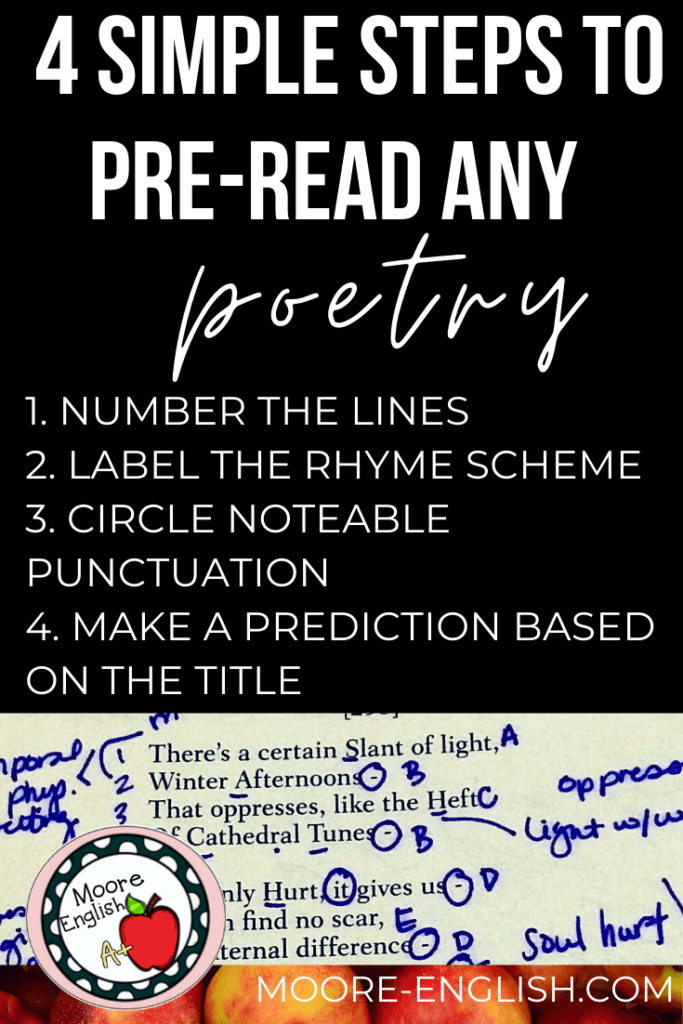

Everyone loves TPCASTT. It’s a good acronym to guide students through the process of reading poetry. But oftentimes my students are so intimidated by poetry that they can’t even get started.

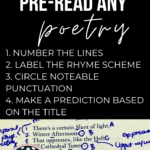

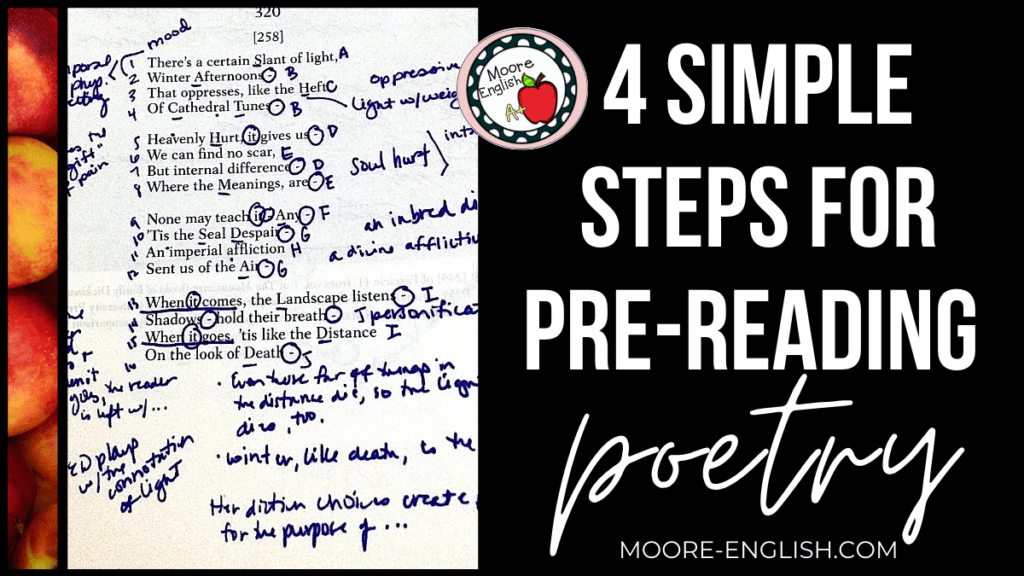

So I teach my students these four steps before reading a poem. Each one of these steps is designed to help students break down a poem so it becomes less intimidating. These steps work for ANY poem and empower students to take ownership of a text. In addition, each step sets students up for quality annotations and helps them see the inner workings of a poem.

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

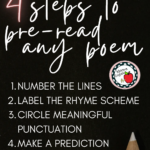

1. Begin Pre-Reading Poetry by numbering the lines.

This seems obvious, but numbering the lines helps students make the text knowable.

Additionally, numbering the lines puts all my students on the same page. So when students are discussing a text, they don’t have to stop, count, and then offer a piece of evidence.

2. Determine the rhyme scheme.

For my freshmen and sophomores, determining the rhyme scheme is a new skill. So all they have to do is label and begin to draw inferences based on the rhyme scheme. For example, if a text begins and ends with the same rhyme scheme, readers might infer that the poem comes full circle. But if the poem ends with a broken rhyme, readers might infer that the poem ends in disharmony. Some options for 9-10 readers working on this skill include:

- “To a Waterfowl” by William Cullen Bryant

- “Richard Cory” by Edwin Arlington Robinson

- “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar

My juniors build on this skill set by considering the basic meter of the poem, including making inferences about breaks in meters. In particular, junior year is when my students and I begin to discuss what meter and rhyme reveal about an author’s historical context. When the writer breaks the meter, what might he or she be trying to communicate? What kinds of emotional content would cause a metrical break? Some options for juniors working on this skill include:

- “The Ebb and Flow” by Edward Taylor

- “The World is Too Much with Us” by William Wordsworth

- “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” by Walt Whitman

Finally, my seniors move into full-on scansion, counting the feet, identifying the meter by its name, making determinations about where and how a writer uses iambs, dactyls, and trochees, etc. As my students become more sophisticated with scansion, they are able to have more robust discussions about the writer’s choices. Some options for seniors working on this skill include:

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets

- “Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant

- “Time does not bring relief; you all have lied” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

3. Circle any notable punctuation (final punctuation, dashes, parentheses, semicolons, colons)

Punctuation can reveal a tremendous amount about a poem. For example, the use of dashes is almost always essential and noteworthy. Before even reading the poem, students can begin to make inferences about where the turn or shift is going to occur. Different types of punctuation can have different effects on a poem. So I created this handout to help my students decide the meaning of a piece of punctuation.

Some options for helping students work on this skill include:

- “The Summer Day” by Mary Oliver

- “The Second Coming” by William Butler Yeats

- “I heard a Fly buzz–when I died” by Emily Dickinson

4. Finish Pre-Reading Poetry by going back to the title.

Before we begin reading and fully annotating the text, students return to the poem’s title and make inferences about the poem’s content, speaker, and main idea. My students all have to make a prediction about where the poem is going to turn. We usually mark this with a star and a question mark. If their prediction about the turn’s location i s correct, they erase the question mark.

s correct, they erase the question mark.

After a semester of using these four steps, my students feel confident pre-reading poetry. They feel like they can explain the process of annotating poetry to other students. If you’re interested in using these strategies in your classroom, check out this set of Poetry Pre-Reading handouts, worksheets, and bookmarks. What strategies do you use to help your students annotate poetry? Leave your suggestions in the comments!