This summer has been full of uncertainty and doubt. In part, that comes from the coronavirus. But that also comes from concerns about social justice in the classroom. Educators are asking: “How can I move my classroom from a place of being not racist to being antiracist?” I’m learning a lot. There have been set backs, transitions, mistakes, apologizes, epiphanies, realizations, and prayers along the way. And there will be more to come.

In reading and studying, I’ve worried about intellectualizing the work of antiracism, consuming Black stories without recourse, and/or only thinking about antiracist work in the abstract. The task of dismantling white supremacy is enormous and can feel overwhelming. Where do I begin? How do I begin? And how do I turn what I have learned into concrete actions?

Well, an early attempt to diversify my reading list led me to Colorlines, a Race Forward publication, which describes itself as ” daily news site where race matters.” Prior to this year, I’d never heard of this website before. But now it’s part of my regular reading*. Recently, Samuel Sinyangwe from Colorlines wrote an article called “Here’s How to Find Out How Racist Your Kids’ School Is.”

In the article, Sinyangwe writes about using data from the Department of Education to advocate for antiracist change in education. Overall, Sinyangwe gives very clear directions, suggestions, and steps for taking actual data about your school and your students and turning it into change.

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

What I Learned and What I Asked

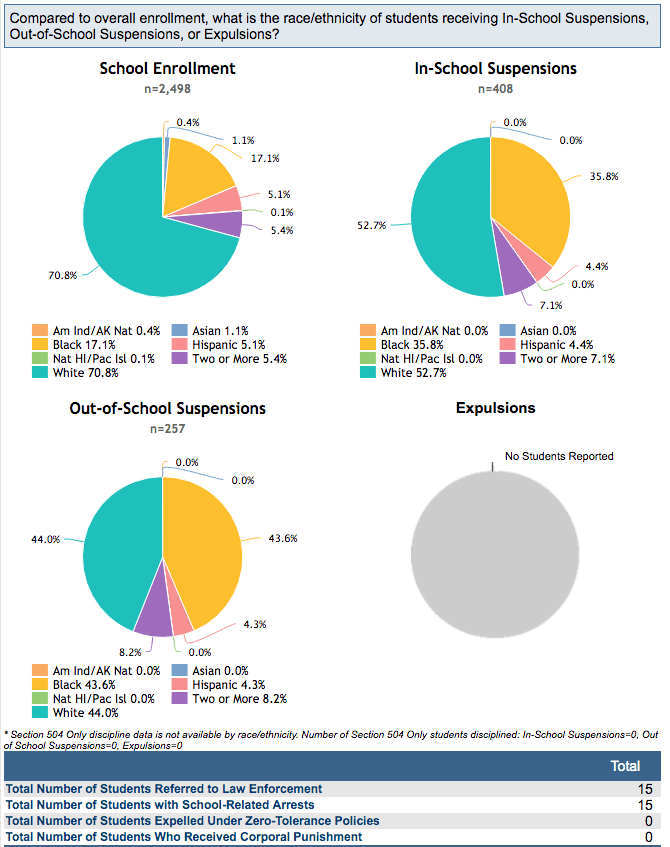

In taking Sinyangwe’s advice, I learned this about my school. In my school, 70.8% of students are white and 17.1% of students are Black. As Sinyangwe points out, white and Black students are likely to commit similar infractions at similar rates. However, in my school 52% of In School Suspensions (ISS) went to white students while 35.8% went to Black students.

I’m not an expert in antiracism. But I am an expert in breaking down and analyzing data. This data suggests a racial disparity in the distribution of discipline.

Here are some things to consider in evaluating this data and some questions to pose as a result of this data:

- Firstly, where does the initial disparity occur? ISS is not something teachers can assign themselves. ISS can happen in a few ways, but there are two significant paths to ISS: the Big Incident and the Series of Incidents. For example, a Big Incident would be something like a physical altercation, making a threat, or juuling in the bathroom. A Series of Incidents would, most likely, be a recurring set of behaviors reported by one or more teachers through repeatedly issuing discipline referrals.

- In the case of a Big Incident, discipline actions are pretty well dictated by a matrix of responses. First Big Incident? Here’s the matrix-approved response. Second Big Incident? Here’s the next matrix-approved response. Rather than ask “Does racism affect the implementation of the matrix?,” let’s acknowledge that white supremacy is everywhere, and standardized responses to misbehavior may be an expression of white supremacy. Rather than ask “Does…,” let’s ask, “How does racism affect the implementation of the matrix?”

- In the case of a Series of Incidents, it’s a lot easier to see how racism could seep into this process. Teachers can write discipline referrals for basically anything. So, let’s again ask “How does racism affect discipline at the classroom level?” Let’s ask: “How can teachers, especially white teachers, work to mitigate+ the effects of racism on classroom-level discipline?” And let’s ask: “What kind of training and cultural change is needed to make positive and significant change?”

Concrete Actions for Antiracism

Finally, addressing racism in school discipline is enormous and essential reform. It’s also a small part of making societal reforms. In his article, Sinyangwe makes some suggestions for using your school’s data to advocate for change. I want to add three more resources I found helpful:

- Firstly, Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance) has provided A Guide for Administrators, Counselors, and Teachers called Responding to Hate and Bias at School.

- Secondly, Rick Wormeli writing for Educational Leadership also has an article called “Let’s Talk about Racism in Schools.” In particular, the article ends with a series of principles and questions that can be helpful in guiding discussions about racism in schools.

- Thirdly, as I was writing and revising this post, Andrew Ford wrote “How to Use Data to Advance Racial Equality in K-12 Schools” for Edutopia. Ford offers three equity principles that teachers and schools can use to focus on making schools a welcoming place.

Although this post is in the first person, my goal is not to make myself out to be an expert or to center my experience. I appreciate the irony of that and hope that these reflections and suggestions can help other teachers. There’s so much in the world of antiracism where I don’t know what to do or how to begin. I really debated publishing this post even. And I haven’t posted on Instagram in months because I don’t know how to be in that space right now. Everything I consider feels hollow. However, data is something I understand, so I hope this post encourages you do consider your school’s discipline data and to consider options for moving forward.

*I read a lot. From everywhere. Here, here, here, and here are past collections of my varied reading habits.

+I went back and forth on this word choice a lot. “Mitigate” vs. “erase”? Ultimately, I chose mitigate because dismantling the system of white supremacy while white means you’re (and so am I) also benefiting from that system.