Oftentimes, textbooks about literary criticism group mythological and archetypal criticism. For more advanced students, this grouping makes perfect sense. However, at the high school level, grouping these two critical lenses together can often create a greater sense of confusion for students.

For this reason, I have learned to approach mythological and archetypal criticism as two seperate lenses. Today, I want to share some of my favorite texts for teaching archetypal criticism.

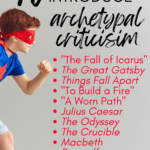

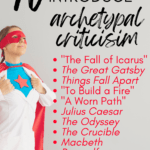

Introducing Archetypal Criticism

Even if literary criticism isn’t new for students, the term “archetype” is daunting! To help students unpack this term, I often use this set of free Defining Heroism Task Cards. Each card features a well-known hero from popular culture and a brief description of their characteristics and story. Students evaluate the cards in a small group, trying to identify common characteristics of heroes.

With inquiry-based learning, students are engaged quickly. Using familiar characters also helps students connect literature to their “real” lives. After each group of students has a list of heroic characteristics, we begin making a giant list on the board, starting big and then narrowing it down until we have six or so characteristics.

Then, I introduce the term “archetype” through direct instruction and give examples of several archetypes. Young adult literature is full of archetypal characters (the jock, the mean girl, the quiet kid, etc.), so students usually pick up the concept quickly.

Short Works for Archetypal Criticism

Even as high schoolers, my students love mythology! The Percy Jackson books in my classroom library are always in circulation, so mythology is a great place to begin discussing archetypal criticism. With this in mind, we might read “The Fall of Icarus.” Since mythology is often written for elementary and middle-school students, I worked to find a more high-school appropriate version and chose this adaptation by Josephine Preston Peabody. Icarus fits several archetypal characteristics, and a familiar story is often a good place to begin.

An important part of archetypal criticism is the hero’s journey. To discuss the hero’s journey, I like to introduce two different heroes and their travels. First, “A Worn Path” by Eudora Welty is a great text for both archetypal and mythological criticism. My students usually sympathize with Phoenix Jackson and have strong opinions about the text’s use of deliberate ambiguity.

In contrast, my students usually hate the man in “To Build a Fire.” Unlike Phoenix, the man’s motivations are greedy, so he makes for a perfect discussion of hubris. Reading these two texts side-by-side can reveal different facets of the heroic archetype and can introduce the term anti-hero.

Longer Works for Archetypal Criticism

Sometimes it’s helpful to see the hero’s journey play out over a larger text. These four options provide students with the opportunity to see more “episodes” in a hero’s journey.

First, The Odyssey is a text my students read as freshmen, but it can also be a good text for archetypal criticism. Odysseus’ journey sets the blueprint for the Western version of the hero, and his story is straightforward enough to act as a good starting place. Read more about how I teach The Odyssey:

- Stations for Introducing The Odyssey

- 9 Paired Texts for Teaching The Odyssey

- Cognitive Thinking and Collaboration with The Odyssey

Similarly, Beowulf is another epic journey. The scope of Beowulf’s travels and monstrous battles always keeps students engaged. Perhaps more than Odysseus, Beowulf undergoes significant character development that can make archetypal criticism more complex. As Beowulf encounters Grendel and the dragon, I often introduce this think sheet to help students differentiate between hero and anti-hero. Grab my abridged and modified Beowulf today!

Unlike Beowulf, the main characters in The Great Gatsby and Things Fall Apart do not grow or change. As much as readers want Gatsby and Okonkwo to become fully dynamic characters, neither can rise to the occasion. For this reason, these novels provide students with a perfect opportunity to apply archetypal criticism.

Using Drama

Oftentimes dramas are the places where students encounter the most overt archetypal characters. For many of my students, Shakespeare’s dramas are the first place they learn about the term “archetype.”

As sophomores, my students read Julius Caesar. While there are many aspects of this play that I adore, in the context of archetypal criticism, this play does a fantastic job setting up parallel characters in Caesar and Brutus. Evaluating their dualities is a great way to help students understand how author’s intentionally design characters to foil, reflect, and comment on one another.

Similarly, my juniors read The Crucible by Arthur Miller and encounter Thomas Putnam and John Proctor, the later of whom is the archetypal tragic hero. The differences and similarities between these two characters provides a rich dialogue for building upon the reading students did as sophomores.

Finally, as seniors, students read Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which is an ideal way to end their study of archetypes because this text includes so many. From the witches to the porter to Macbeth and his wife, this play is full of archetypal figures, each with conflicting motives and goals.

What texts do you use to teach archetypal criticism?