Yesterday, Danielle Valentin asked me a great question on Twitter: What’s the best way to assess close reading?

According to Beth Burke, NBCT, close reading “is thoughtful, critical analysis of a text that focuses on significant details or patterns in order to develop a deep, precise understanding of the text…”

In other words, close reading engages in a meaningful dialogue with the text. Oftentimes, we facilitate that conversation through annotation. But Carol Jago and Penny Kittle remind us that “Annotation is not close reading; it is a habit of the mind.”

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

Similarly, Dave Stuart Jr. reminds us that annotation is only valuable when it has purpose. This means, as teachers, we must intentionally plan for how annotation will appear in our lessons.

Additionally, we must also make sure students understand the purpose for annotation in our lessons. If we incorporate annotation into our lessons in service of close reading, then we must ask ourselves how the assessment measures students’ ability to close read. Therefore, we must return to Danielle’s original question: how do we assess close reading?

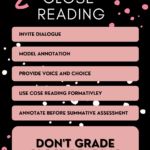

With that question in mind, here are 5 Dos and 1 Don’t for assessing close reading:

How to Start

DO model close reading and share your thinking with students. Before students can begin the process of close reading with rigor, it’s important to walk students through the process. Let them see and hear your dialogue with a text.

My favorite ways to support close reading involve using easy-to-remember systems. For poetry, I use this system and these tools. And for informational and nonfiction texts, I use this system and these tools.

For my juniors, I model close reading with the first paragraphs of Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Choose a text that presents frequent opportunities for students to wrestle with meaning. Build in an opportunity for you to self-assess your work in front of students. So you are modeling the reflection process for them, too.

DO invite dialogue. My absolute #teachertruth is that reading is a conversation, and writing is a social activity. With this philosophy in mind, I fully believe that close reading is a conversation with a text. Students have to bring their insights into the text and make room for the text’s impact.

For Peter Elbow, this is the “violence” involved in learning: to make sure that both student and text are “maximally transformed–in a sense, deformed” (331). Close reading should invite a chorus, a cacophony, a conversation!

Incorporate meaningful academic discussion into your lesson. Ask students to establish some behavior norms for discussion. But then let them dig into the text together. The assessment comes from your observations, student responses to each other, and student responses to your questions.

Use Close Reading to Support Assessment

DO use close reading as formative assessment. While my students are discussing a text, I ask them to have their annotations out. As they chat, I walk around and read through annotations. If annotation is your tool for assessing close reading, then you have to be reading over students’ annotations to make sure they balance critical thought with comprehension. This can be a hard balance to strike, which is why modeling is so important.

As I walk, I star great insights and write questions where students missed an opportunity to extend thought further. After a discussion, I encourage students to share their reflections on their annotations. If I consistently see a student struggling to create meaningful annotations, I will do a mini-lesson and reteach as needed.

DO use close reading as a platform for summative assessment. Close reading draws on inference, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation skills! Because close reading requires so many higher-level skills, it is a great platform for diving into a summative assessment.

In writing, close reading is an important part of peer revisions and feedback. But the summative assessment is the writing.

During Socratic Seminar, close reading is essential to generating meaningful questions. But the questions and dialogue are the summative assessment.

In reading, close reading is critical to providing a nuanced poetry study. But student responses to the poem (maybe in the form of multiple-choice questions or a short answer) are the summative assessment.

Get Creative

DO incorporate voice and choice into close reading. In my classroom, close reading almost always means annotation. However, instead of insisting that students use one standard annotation format, we experiment with a variety of formats: double-entry journals, Cornell notes, and post-it-notes.

Sometimes we annotate digitally, use Screencastify, or mark directly on a piece. After students try a certain number of annotation styles, they can choose the one that fits their needs and their mind. Invite creativity into this process!

But annotation isn’t the only marker of close reading. Students can complete exit tickets, color-code a text, design graphic organizers, free write, or journal. Each one of these items can be an assessment of close reading.

Assess Close Reading Without Grading

DON’T grade close reading. Close reading improves student comprehension, engagement, and higher-level thinking. However, close reading is not the summative assessment. So there’s no need to put a grade on close reading. Remember, “grading” and “assessment” are not synonymous.

As Carnegie Mellon University indicates, assessment seeks to “improve student learning” while grading is evaluative. Close reading is an assessment of how well a student interacted with a text and can be measured with annotation. However, the goal of close reading, like the goal of assessment, is to improve student learning. Grade the final copy. Grade the Socratic Seminar. And grade the item, task, or product that shows the culmination of student learning.

What close-reading strategies work in your classroom? What other questions do you have for Moore English? Send your questions, and remember to subscribe for new posts every week.

Photo by Debby Hudson and Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash