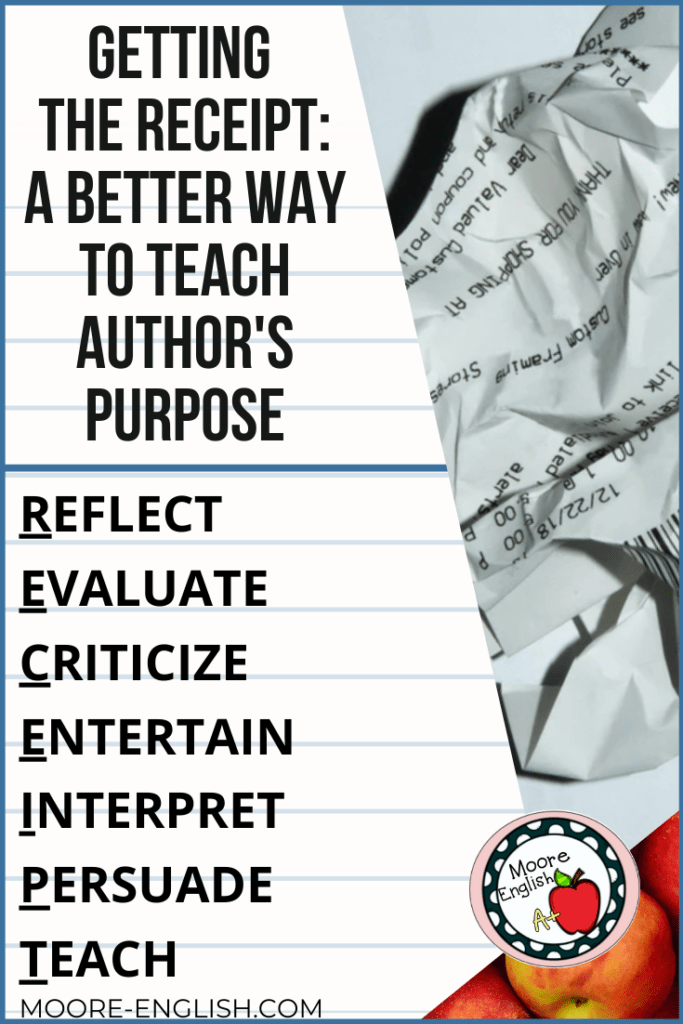

Let me make a confession: A few years ago, I got very invested in the drama between Taylor Swift, Kanye West, and Kim Kardashian. For me, one of the biggest take aways from that drama was the phrase “Show me the receipts.” I’d heard my students talk about “receipts” before. But something about the Kanye-Taylor drama really made that phrase memorable to me.

As a teacher, I turned that phrase over in my mind. Where are the receipts in the English classroom? Well, when students are looking for author’s purpose, they are looking for the receipt!

Until this year, I’d used the classic P-I-E to teach author’s purpose. But I’d long found that acronym to be limited. P-I-E lacks nuance. It doesn’t meet students’ needs as they begin to read more complex texts.

That’s where getting the receipt comes in! “Receipt” is my new acronym for teaching author’s purpose. It offers students the chance to analyze texts at greater depth. Check out the tools I use to accompany this concept here.

Get the Receipt to Determine Author’s Purpose

In an effort to help students analyze author’s purpose at greater depth, consider introducing them to getting the RECEIPT! This is an easy acronym that provides readers with more purposes from which to choose!

R- reflect

E- evaluate

C- criticize

E- entertain

I- interpret

P- persuade

T- teach

Reflect

Sometimes author’s write from the heart. Authors may be looking to think metacognitively or to grow from a personal experience. The use of first-person is often a sign of reflective writing. And reading reflective texts in class provides students with models for their own self-reflection. Poetry is deeply personal. So reading poems is often a great way to include reflective writing in class. Here are some reflective titles to guide students at all levels.

- “Making a Fist” by Naomi Shihab Nye

- “What I Carried” by Maggie Smith

- “We Lived Happily During the War” by Ilya Kaminsky

- “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wall-paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

Evaluate

Other times, authors write to evaluate. These kinds of texts are some of my favorites to use to as mentor texts to scaffold more organized writing because evaluative texts establish criteria for success. Then, the writers evaluate an idea, a choice, or an action through the lens of those success criteria. These kinds of thinking helps students build their inference skills and prepares them for more organized writing.

There are lots of ways to approach teaching evaluative literature. A mentor texts for evaluative literature is Defining World Literature in which the writer establishes criteria for “world literature.” A more challenging mentor text is Aldous Huxley’s “Words and Behavior,” in which Huxley establishes criteria for good and bad discourse.

Additionally, task cards are a good way to help students practice taking on the role of evaluator. For example, with the Defining Heroism Task Cards, students use the criteria of “hero” to determine which characters qualify.

Similarly, literary criticism is evaluative in nature. A literary critic views a text through a specific lens and determines how successfully the text meets the needs of the lens.

Criticize

Like evaluative literature, criticism makes a judgement about the success of an idea, action, or choice. Evaluative literature, however, makes an attempt at objectivity by providing criteria for success. Critical writing is much more opinion based. Some mentor texts for critical writing include:

- “Credo: What I Believe” by Neil Gaiman, in which Gaiman criticizes the terrorists behind the Charlie Hebdo shooting

- “Shooting an Elephant” by George Orwell, in which the speaker criticizes British imperial rule of India

- “The Danger of a Single Story” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a Ted talk, in which Adichie criticizes blind support of single stories

Of course, my students’ favorite part of critical reading is the application! My students love to share their opinions and to criticize ideas, choices, or actions with which they don’t agree! One way students get to practice critical writing is through producing their own book reviews.

Entertain: My Students’ Favorite Author’s Purpose

This is probably my students’ favorite type of writing! Entertaining writing often follows a more traditional narrative structure. So when my students are working on this author’s purpose, we look for story elements. These include plot and conflict, characterization, and figurative language. Some mentor texts for writing that entertains include:

- The Odyssey: What could be more entertaining than a Cyclops, mythical monsters, and a 10-year trek home?

- The Great Gatsby: Or, as Buzzfeed recently said, “A grifter catfishes a whole town to win back his ex.”

- Pride and Prejudice: Or, as the same article says, “A guy spends a year negging a woman and paying her family’s debts.”

Interpret

This is the genre in which my students spend the most time. Literary analysis is a matter of interpretation. So it’s important that students see lots of experienced authors engaging in interpretation. And it’s equally important that students try their own hand at interpretation. Some opportunities for students to try interpretation include:

- “Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant, which my students always connect to Thanos in the Marvel Universe

- The Crucible by Arthur Miller, which my students love to interpret because the characters are so divisive

- “A New England Nun” by Mary E. Freeman, which has a polarizing ending students long to discuss

Persuade

Persuasive writing is complex because it draws on so many other types of writing. When an author’s purpose is to persuade, they also have to be adept at several other types of writing. When an author’s purpose is to persuade, they might use rhetoric and loaded language. Perhaps my favorite mentor text for persuasive writing is Mark Antony’s oratory in Julius Caesar. But Atticus Finch’s courtroom speech is a close second! When students start digging in to their own persuasive writing, task cards can provide a great opportunity to classify and analyze rhetoric. Some other mentor texts include:

- “Privileged” by Kyle Korver

- “The Crisis No. 1” by Thomas Paine

- “Speech to the Virginia Convention” by Patrick Henry

- “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” by Jonathan Edwards

Teach

This genre is so interesting because it encompasses so many author’s purposes. “Teaching” includes informational, explanatory, and expository texts. This genre also has so many clear “look fors” including text features and research. This is also a great place to practice reading and annotating informational texts for author’s purpose. Some informational texts that “teach” include:

- “The Immigrant Contribution” by John F. Kennedy, in which JFK explores the role immigrants have played in developing America and the American dream

- “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” from The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois, in which Du Bois explores the double consciousness

Bottom Line: Author’s Purpose is More Complex than P-I-E

Overall, determining author’s purpose is far more complex than P-I-E. Encouraging students to get the “receipt” reflects the nuance needed to analyze a complex text. To help you bring the receipts into your own classroom, I’ve put together this collection of notes charts, book marks, and anchor charts available in .pdf and Google Slides! Of course, as students develop more and become stronger readers, they leave behind the idea of receipts all together.

Photo by Michael Walter on Unsplash