The first few times I taught American literature, I skipped regionalism. Each time, I told myself that I just didn’t have time. However, in truth, I didn’t have a good definition for regionalism or a way to explain its impact to my students.

However, two years ago, I committed to making space for regionalism in my American literature class. And, wow, I am shocked at how much of a difference this has made for my students.

Incorporating regionalism has had three key benefits for my students:

- First, it really helps students bridge the gaps between Romanticism, Realism, and Modernism.

- Second, regionalism features lots of women writers, and it helps create greater space for women writers in the curriculum. Is there room to improve? Always. But this is a place to start.

- Finally, our study of regionalism appears late enough in the year that it’s a great place to introduce literary criticism.

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

If You Only Have Time for One Regional Text…

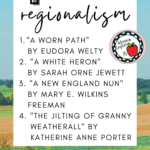

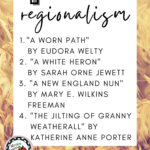

Sometimes there is simply not enough time to teach everything you want! So if you only have time to incorporate one piece of regionalism, then I recommend “A Worn Path” by Eudora Welty. Read it here.

First, this is a short short story with a straightforward plot: Phoenix Jackson needs to go to town to get her grandson’s medicine and encounters various symbolic obstacles along the way.

Second, “A Worn Path” lends itself to a straightforward formalist reading of the symbols and hero’s journey. The text limits all its deliberate ambiguity to the ending: will Phoenix make it home? And when she gets home, is her grandson alive? This means that even students who struggle to wrap their minds around regionalism will be engaged in the text.

Finally, “A Worn Path” features all of the key elements of regionalism, so if it’s your only chance to touch on this literary movement, you have everything you need. Similarly, this is a great text to introduce regionalism. I have put together an acronym to help students remember the characteristics of regionalism.

Spending a little more time on regionalism?

If you have time to study a second piece of regionalism, Sarah Orne Jewett’s “A White Heron” is an excellent choice. Like “A Worn Path,” this short story features a straightforward plot. While “A White Heron” is a longer story, its symbols are crisp, and the main character’s internal conflict makes for great student conversation. Additionally, “A White Heron” touches on the key features of regionalism. Read it here.

Furthermore, “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” by Katherine Anne Porter is a good text for helping students see the transition from regionalism to modernism. The rural setting, Granny’s values, and traditional elements of the text fit regionalism well. However, the stream of consciousness signals the influence of modernism. This is a good transition piece for students! Read it here.

Finally, my favorite regional text is “A New England Nun” by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman. The ending of this story is always a great conversation for students: is Louisa free? Or is Louisa still trapped? Either way, Freeman’s text helps students move from Romanticism to regionalism. The local color in this text is evident! Read it here.

Expanding Your Study

For me, regionalism is often a window into literary criticism. As my students work through these texts, we discuss different critical perspectives.

Because we have been discussing regionalism, making the stretch to historical criticism is fairly straightforward. Students consider how the text’s historical context(s) appear in the text and what the text itself reveals about the times in which it was written and takes place.

Though it may seem counterintuitive, Marxist criticism fits well with historical criticism because of the way socioeconomic forces interact with historical context. In particular, social class plays a significant role in “A Worn Path” and “A White Heron.”

Similarly, all of these texts lend themselves to feminist criticism. In each story, the main character’s agency is compromised not only by her assigned gender roles but by an additional identify. Phoenix Jackson is Black during Reconstruction. Sylvie is a child interacting with adult economic forces. Granny Weatherall’s age and health have caught up with her, and Louisa is constrained time and time again by social and personal forces.

Finally, “A New England Nun” lends itself to deconstructionist criticism. Is the text a liberation for Louisa, or is she further constrained by the storytelling itself? It’s a challenging but rewarding conversation to have with students. In fact, “A New England Nun” is included in my Deconstructionist Criticism Bundle.

To make your life a little easier, I have included all four of these short stories in my Regionalism Bundle! With this resource, teachers can make sure they’re always including regionalism in their study of American literature.