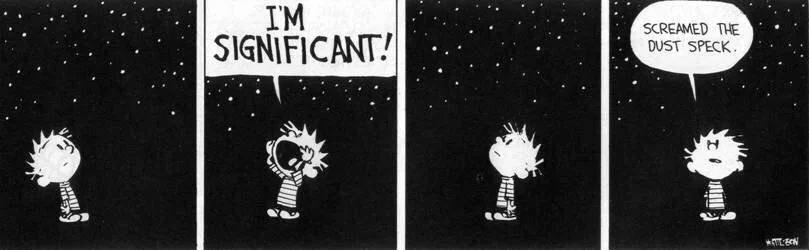

By the time my juniors arrive at American literary Realism, they are familiar with the concept of literary periods and movements. To keep students engaged, I like to begin the unit with this comic from Calvin and Hobbes. (I can’t take credit for finding this comic. A past student sent me this way. Nor, obviously, do I own Calvin and Hobbes.)

Anyway, when we begin Realism, I show students this comic. I explain that this comic encapsulates some of the conflicts central to Realism. Then, I ask them to make predictions about the characteristics of Realism.

Students think-pair-share their answers, and we write them up on the board. Before you go forward, try this out for yourself. See how many characteristics of Realism you can name! Then, keep reading for everything you need to cover American literary Realism.

This post this post may contain affiliate links. Please read the Terms of Use.

Engaging in Realism

One of my favorite ways to engage students in a new topic is through the use of an anticipation guide. I employ this Realism anticipation guide the same day that we evaluate Calvin and Hobbes. Students think-pair-share their anticipation guide answers. Then, we re-visit our list of potential Realistic characteristics on the board, adding and eliminating as needed.

Another great way to engage students in Realism is to set up some engaging essential questions. Some strong questions for this unit include:

- How can we improve a world that lacks heroes?

- What role do humans play in the greater universe?

- How can storytelling be used as a way to improve the world?

- What kind of obligation do humans have to the environment?

Essential questions are great because they can appear throughout the unit and act as touchstones for discussion, writing, and evaluation!

- First, teachers can use the essential questions to spark classroom discussions.

- Second, students can journal in response to essential questions, perhaps updating their reactions to the questions throughout the unit.

- Finally, at the end of a unit, teachers can turn any of the essential questions into a written summative assessment. Students can draw on the readings from the unit as evidence to address the prompt. (Grab my favorite rubric!)

Realistic Poetry

When choosing texts for this unit, I focus on literature that feels radically different from our earlier studies of the American Enlightenment, Romanticism, Regionalism. For me, one of the most important part of Realism is the way it reacts to, rejects, and pushes against the traditional beliefs of earlier writers and speakers.

In particular, two Realistic poems stand out:

- First, “War is Kind” by Stephen Crane rejects any romanticism of war. The Civil War casts such a long shadow over Realism, and this poem does a good job showing how war can disillusion its survivors and victims. The repetition and irony in this poem make it an ideal piece to analyze as a class, and the structure is not traditional but is not so experimental that it throws students. Read it here.

- Second, “In Heaven” by Stephen Crane more directly rejects Romanticism itself. While grass is a familiar symbol from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” the grass in Crane’s poem symbolizes something quite different. Reading those two poems within a short period of time helps students see how Realism distances itself from earlier generations. Read it here.

Grab both of these poems in my Stephen Crane Poetry Pack!

Realistic Short Stories

More than anything, I associate Realism with Jack London’s “To Build a Fire.” Even if I’m pressed for time, I always try to make space for teaching this short story. Because “To Build a Fire” is so long, I actually use this abridged and modified version.

I also like to show a film version of “To Build a Fire.” These are two great versions:

- First, this thirteen-minute animated version from Nexus Studios is great because it’s so short.

- Second, this fifty-minute live-action version narrated by Orson Welles is my favorite because it incorporates so many elements of the story. The silences in this film help students understand how the author creates mood.

After watching the film version, my students are always eager to discuss this text. The main character is so divisive that students have a lot to say! This is also a great time to revisit the essential questions and to see how students’ opinions have evolved! Read it here.

Additionally, if you have time, “Editha” by William Dean Howells is a compelling piece of Realism. Like the man from “To Build a Fire,” Editha is a divisive character. On the one hand, the text lends itself to feminist criticism, but it also exhibits the characteristics of Realism! Read it here.

Let’s Be Real About Realism

Realism is such a unique period in American literature. While this literary period is relatively short, the historical context is rich, and the impact of Realism is still felt in contemporary literature.

Save yourself some time and energy by grabbing my American Realism Bundle today! Overall, this is a month of teaching resources ready for you to use today!